Words are one thing, actions another. The former belong more to the older generation, which tends to think carefully before acting. On the other hand, the young act swiftly, perhaps even before thinking. When thinking about 'green', one often thinks of the Old Continent. Europe, with its programs and rules: Green Deal, Next Generation EU, Taxonomy (hailed as the world's first green taxonomy), SFDR, etc., directives that have also greatly influenced financial investments, with funds classified under articles 6, 8, and 9. In America, however, little has been done to classify sustainable investments, but financial policy measures (IRA) have been adopted to support companies in the sector, leaving investors to assess the profitability of companies affected by new rules. The result is that while Europe talks, America acts. Thus, even in renewable energy, America is poised to surpass Europe, despite the latter's claimed leadership in words.

Politically, things seem to confirm this trend: the United States is becoming more politically green, while Europe is backtracking. One can read Kamala Harris's candidacy for the White House in this light, which has revitalized the renewable sector, previously at risk due to a potential easy victory by Trump. Conversely, Europe has seen a series of political elections that have favored right-wing parties and a progressive decline of the left, particularly the Green parties, as seen in the European Parliament, Germany, and most recently Austria. It's striking to note that a global leader in construction has stated that Germany has not invested a single cent in green infrastructure, despite Germany's self-proclaimed leadership in green initiatives, shutting down nuclear plants ahead of others but witnessing the Green party halve its support, leading to the recent resignation of its leaders.

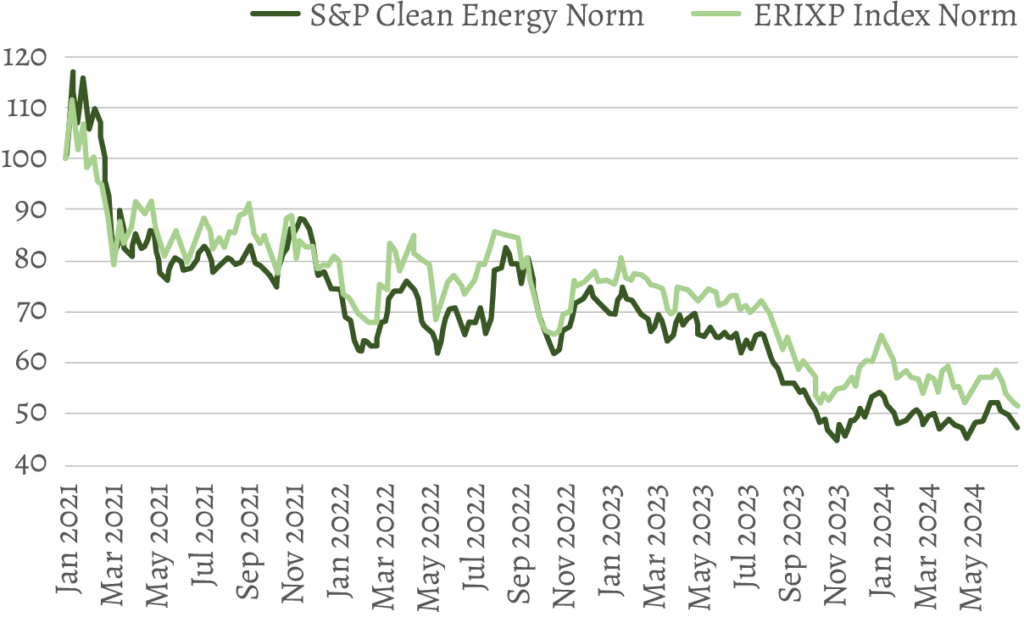

Notably, the global renewable index, like the S&P Clean Energy, led by US solar companies, has recovered much of its losses this year (though still negative for the fourth consecutive year), registering around a 5% loss by the end of September, whereas a distinctly European renewable energy index, the ERIXP Index, lost 25% in the same period. Considering that until the European elections last June, these two indices had nearly identical trajectories over the past three years, one gets the sense that despite Europe's self-proclaimed global leadership in green investments, it fails to garner investor support. Conversely, in the United States, investors approach the green sector purely for profit, without ideological influence. From this, it can be deduced that US policies, while not sharply distinguishing between green and traditional investments, are more effective than European policies, which must adapt to ongoing changes such as those regarding nuclear and gas in the Taxonomy.

An example of the ineffectiveness of European rules can also be seen in their ability to channel investments towards truly green policies, i.e., combating greenwashing, something the United States handles well due to its more speculative rather than ideological approach. The proliferation of funds classified under Article 8 in Europe confirms this: a fund in this category can invest in almost the entire European market. It's difficult to find companies not considered green; it has been reiterated several times that the STOXX 600 ESG contains more than 560 stocks compared to the traditional index's 600. If fund investment policies introduce even a minimal percentage of non-green investments, the game is won. In contrast, Standard & Poor's has performed better with its flagship index, the S&P 500 Index, whose ESG version excludes 30% of companies.

At least on this front, Europe is trying to make amends. In the names of funds that do not hold at least 80% sustainable assets, terms related to 'green' such as 'ESG', 'Sustainability', 'Transition', and the like will be prohibited. Such words will only be allowed for funds classified as Article 8 with at least 80% sustainable assets, and for those classified as Article 9. However, this change must be accompanied by maintaining the goals set for 2030 and 2050, despite challenges posed by wars, inflation, and the consequent rise of right-wing parties in Europe. The potential reconfirmation of Von der Leyen, despite the debacle of the Green parties, could represent a stabilizing and guaranteeing element for the future of green policies.

US: -25, -6, -22, -14; EU: -19, -6, -14, -22. We are not giving lottery numbers, which at best would be positive, but rather the annual percentage performances from 2021 to 2024 (for the latter, it’s the performance for the first six months of the year) of the S&P Clean Energy Index and the ERIXP Index, two indices that measure the global and European trends of companies related to renewable energies, respectively.

We are therefore in the fourth year, though not yet complete, of a decline in the renewable energy sector. And it doesn’t matter if we look at Europe, the United States, or globally, the trend of this asset class is similar in every region (see chart).

Renewable Energy

Source: Refinitiv

Yet governments have done a lot, from the Green Deal in Europe to the IRA in the US, to promote sectors related to this theme. Additionally, private investments have also been substantial: in 2023, investments in solar alone surpassed those in oil; when adding other green sources, the difference significantly favors the latter.

So, are we all wrong? Perhaps a distinction needs to be made between traditional financial investors, institutional or retail, whose investment horizon seems not to extend beyond the end of the year, and those who invest because their livelihood depends on energy or because they can afford to evaluate companies in the medium to long term: we’re talking about companies operating in fossil energies, which want to diversify their portfolio by adding more renewable energy, and private equity funds, which seize opportunities that others probably do not see.

Small and medium-sized enterprises entirely operating in renewable sectors, which have been and still are a joy for the short positions of hedge funds, and not only, have reached values so low in recent months that they have attracted the attention of investors interested in alternative energy. Not surprisingly, there have been three acquisition or joint venture operations in Europe over the past three months. In mid-March, the private equity fund KRR launched a takeover bid for the German wind and solar park operator Encavis, at a price that exceeded its market value by 40%. At the end of the same month, SLB, the world’s largest oil services company, signed a joint venture to acquire 80% of Aker Carbon Capture shares at a price almost 60% higher than its market quotation. Finally, in May, the Swedish private equity fund EQT launched a takeover bid to purchase the fellow Swedish company OX2, operating in renewable energies, valuing it 43% more than the market.

To these operations, significant stakes in small and medium-sized companies, still in the renewable sector, by large companies in the fossil field can be added. For example, Equinor, which continues to accumulate Scatec shares whenever the price of the Norwegian company operating in solar and wind in emerging countries falls to values considered low. Currently, Equinor holds more than 16% of Scatec's shares.

These investors, therefore, are paying on average 50% more than market values for these small and medium-sized companies, with the idea of making a profit. One must wonder if they are being too reckless in their dealings or if traditional investors are missing some information.

To get an idea of where the truth lies, we can consider the performance of ETFs related to indices similar to the S&P Clean Energy, preferred instruments for tracking the performance of renewable energies by traditional investors: in the past two months, this index recorded a performance of +13% in May and -11% in June. This volatility, in such a short period, highlights at least two things: the first is that the approach to this theme is indeed made through generic instruments like ETFs, in which there are often companies developing very different green technologies; the second is that investment in this area seems more driven by emotions than by a vision, whether positive or negative, of the future of these types of energy.

Europe has made its decision. Arms are, in fact, a necessary sector for its own survival, and therefore a sustainable one. Already in November last year, the European defence ministers issued a joint note to this effect. Since February, even Von del Leyen, the prime champion of the European energy transformation, has given her blessing to weapons, stating that two million munitions will be produced by 2025 and that investments are needed to equip a European army of its own. The possible appointment of a European Defence Minister also goes in this direction. So far so good, member states must support defence, no problem. The controversial part is to demand that these investments should not only be governmental, but also private. Hence, the influx of ESG, or sustainable, investments in favour of weapons.

With this move, Europe is losing its credibility. Born as a promoter of green investments, the progenitor of the European Taxonomy, hailed as the vademecum of sustainability, the Von der Leyen-led Commission first included gas and nuclear in it, after the European Parliament had branded them as unsustainable, and is now seeing to it that Defence is included in the Social Taxonomy, although there is still some resistance.

Those who believe that a more sustainable world is possible and have espoused the idea of Europe are beginning to be perplexed by these constant second thoughts, dictated by circumstances rather than initial principles and ideas. Those who have written green fund investment policies excluding nuclear, gas and weapons now find themselves displaced, confronted with funds with looser ESG rules and who have only ridden sustainability as a mere passing financial trend, those funds among them guilty of greenwashing. At this point, however, one has to wonder whether these funds are really guilty or have merely anticipated moves that Europe itself is slowly making. Is it therefore Europe itself that is becoming guilty of the same odious phenomenon?

Investment in weapons, moreover, can only reduce the funds allocated to Ecological Transition, delaying it, as well as having a negative effect on GDP, as stated by Greenpeace, which has launched a petition in Italy to stop this war trend.

And all this is happening with European companies struggling to push ahead with those projects so dear to the Transition to Zero Net Emissions by 2050, but which need incentives before technological evolution can make them autonomous. One example is the pilot auction on green hydrogen that took place last February and whose results will be announced within two months, during which the bids submitted, far exceeding the EUR 800 million made available, will be judged on price. According to the managing director of NEL ASA, one of the world’s leading European companies in this technology, this could lead to the collapse of the European green electrolyser sector if these funds go to Chinese manufacturers, who benefit from lower labour costs and government subsidies. The same concern has been raised, in the biodiesel sector, by a German company, Verbio, which has been denouncing Europe for months for always allowing Chinese producers to flood the European market with fake biofuel, putting not only European companies in this sector at risk, but also subsidising forms that can be defined as greenwashing. These phenomena add to the current market environment, where high interest rates hit small and medium-sized European companies investing for the future the hardest, making them unattractive to private investors, effectively driving away the capital that Europe itself had promised to attract with its laws. So while renewable energy and green hydrogen companies continue to flounder on the stock exchange, defence companies multiply their capitalisation by multiples proportional to their investments in weapons.

If this is the Europe of Transformation, perhaps some rethinking is in order.

In December, the annual meeting on climate transition took place. Expectations were high: on one side, Europe reaffirmed its "fit for 55" program, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. On the other side, the promises from the USA and China: both found a common ground in climate, pledging to triple investments in renewables by 2030.

The conference started uphill, with Al Jaber, the meeting's president and CEO of Adnoc, the national oil company of the United Arab Emirates, stating that a failure to use oil would regress the world to primitive conditions. He emphasized the absence of scientific evidence proving that a gradual elimination of fossil fuels could curb global warming.

The final proclamation did not echo unanimous support for climate action. Instead of concluding at noon, the proceedings extended until 3 am the next day. The planned “phase-out” of fossil fuels, favoured by greener countries, faced resistance from oil-producing nations and conference organizers. A middle ground was eventually reached, termed as a "transition away" from fossil fuels, leaving room for doubts and concerns about possible delays from resistant countries. Nonetheless, some see the glass half full, noting it's the first time in a COP that some mention of phasing out fossil fuels has been made.

Optimism also surrounded initiatives such as six major oil companies allocating funds to reduce methane emissions by 2030, a promise to triple investments and double the efficiency of renewable energies by the same year, and the signing of the Global Decarbonization Charter, in which 50 fossil fuel producers commit to zero emissions by 2050. However, this commitment lacks intermediate benchmarks or quantitative checks, making it a voluntary, non-binding limit with no sanctions for non-compliance.

Nuclear energy was also acknowledged as clean energy, with 22 countries pledging to triple nuclear energy production by 2050. After having been considered unsustainable by the European Parliament in 2020, it re-entered in the European taxonomy in 2022 as a transition activity and was eventually declared entirely sustainable in COP 28 in 2023, considering the expected tripling of production by 2050. All this on the backdrop of the Russo-Ukrainian war and threats to the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant.

All these promises and celebratory results – unprecedented in previous COPs – did not alleviate the negative sentiment surrounding renewable energies. The S&P Clean Energy index still showed a -30% performance from the beginning of the year as at the conference's close, and lost -5% while the conference was underway, suggesting investors were sceptical or found promises too vague and far in time.

In contrast, the December 13 FED meeting and the pivot point on interest rates, with a more dovish Powell than expected, buoyed growth stocks, especially renewables – the most affected stocks during the year. In the remaining ten days of 2023, the renewable index mentioned earlier gained over 10%.

Investors continue to be profit-driven, as evidenced by the performance of defence-related companies following substantial government investments in defence due to the ongoing wars. If countries, especially Europe, want to attract private capital into sustainability, they should support their intentions with clear incentives, investments, and programs: these are the weapons at their disposal.

At the end of July, the renewable energy sector once again entered into a downward spiral: in just about two months the S&P Clean Energy Index lost 30% of its value, bringing the YTD loss to -33%, comparable to the significant downturn of 2021, when the same index lost 34%. However, if back then valuations were excessively high, they now seem exactly the opposite.

Investors sentiment started to crack with Fitch’s downgrade of U.S. debt in early August, justified by the high government spending, whose infrastructure plan includes the well-known $469 billion Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and credits for the green transformation. The negative sentiment intensified in early September when offshore wind projects on the east coast were called into question after a battle between construction companies and the New York administration: the former sought greater incentives to support projects burdened by rising costs due to inflation, wages, sudden interest rate increases, and supply chain delays, while the latter insisted on compliance with the signed contracts. As a result, not only were projects suspended in the U.S., but the following auction in the UK for projects to develop 4GW based on the same technology went deserted – a “disaster” for Ed Miliband, the leading candidate from the English opposition for the role of Minister of Energy Security.

Investors’ panic was such that they sold not only shares of offshore wind companies but, throwing the baby out with the bathwater, also of solar and hydrogen-related companies. However, this effect is often due to the buying and selling of ETFs, such as those on the S&P Clean Energy, which include companies involved in various technologies. The selling extended to the point of creating market inefficiencies, which often happen when panic spreads. For example, the Danish company Orsted, a global leader among offshore wind developers, was most affected by the selling (also because other actors are oil companies like Equinor or BP, whose valuations are supported by oil prices). Its stock price fell from over 600 DKK to just above 300, a value that should be compared to the 400 DKK at which analysts price the company’s installed power alone; that’s not about future or under construction projects but completed projects.

Turning to solar, inefficiencies seem even greater: companies related to this technology are seeing costs decrease considerably, with polysilicon dropping from 30 cents per watt at the beginning of the year to the current 10. This reduction more than compensates for the cost increases due to inflation, labor, etc. Nevertheless, the market price of these companies have fallen between 20% and 40% this year, prompting some of them to initiate buyback plans.

As for hydrogen, it has also received support from the U.S. Department of Energy, which has allocated seven billion dollars for the construction of seven hubs deploying this technology throughout the country; despite this, companies have lost an average of over 40% since the beginning of the year.

Certainly, high interest rates and increasingly tight credit conditions weigh on rapidly growing companies in these sectors. Still, there is a sense that many investors have doubted the entire energy transformation, even though Europe and China continue with their programs and substantial resources. Moreover, despite the encountered problems, New York and Britain also have specific goals: the former must generate 70% of energy from renewable sources by 2030, develop 9GW from offshore wind by 2035, and achieve zero emissions by 2040; the latter has set a goal to install 50GW of wind power by 2030, with only 14GW as of now. Considering that it takes four to six years for the auction preparation and wind park construction, it is clear that there is not much time left, and new auctions in line with market conditions are expected soon.

We are moving from the age of abundance to the age of scarcity! So announced Christopher Guérin in July, speaking about the quarterly results of Nexans, a company that builds cables to transport the energy generated by offshore (sea) wind farms to the mainland. In particular, Guérin referred to the commodity that will be the most used in the new sustainable world: copper.

In 2030, i.e. in just six years, the need for this metal will be six times that of today, given its extremely widespread use: in the electric car (which uses six times as much copper as a traditional car), in charging stations, in wind turbines, in photovoltaic panels, in batteries and for electrical grids, including land and submarine cables. If we have called petroleum the black gold, copper will be the future red gold, as it alone will make up more than 50 percent of the metals needed to bring about the energy transformation everyone wants.

However, it is not enough to have sufficient copper in the earth’s crust for the change to take place; it is also necessary for mining companies to extract it at a profit.

A copper from a new mine for the first few years has higher quality and is easily recoverable, while over time its quality deteriorates and mining costs increase. Conversely, it takes about two to three years to expand an existing copper mine and eight to start operating a new one. Taking all factors into account and the average life of a mine, which is around 25 years, the cost for a mining company is around $3.3/lb. and in order to have a profitable investment, the price of copper should be above $4.2/lb. This price was only reached for a few months in 2021, before falling back below this threshold, where it still stands today. To maintain a price above $4.2 for 20 years, the value of copper should grow substantially, in fact it is estimated that the price will have to double in the next few years.

While cost is the main factor for a mining company to be willing to invest large amounts of capital to develop new extraction sites, it is not the only variable to be consider.

To reach the 2050 targets of zero GHG emissions, we will need another 10 to 20 Mtpa (million tonnes per annum). Today we produce 21 Mtpa and in the last two decades production has increased by 8 Mtpa. So, in the next decade, copper production growth will have to almost triple. But it is not enough to have the necessary investments: equipment, personnel and extraction ability are also needed. It is like bringing water to the desert.

It is therefore clear that the era ahead of us is one of scarcity of supply to meet a rapidly growing demand. And as a first effect, the price will rise.

The age of scarcity does not only concern copper, but all metals and minerals related to energy processing, as well as agricultural commodities due to the increasing world population.

In fact, thinking of electric cars and batteries, another essential element is lithium. The same considerations as for copper also apply in this case: more than seven years to get a new lithium mine operational and 6 to 18 months to reach the quality needed to be used in batteries, whose factories, on the other hand, take only one to three years to build.

We could make similar arguments for aluminium, nickel, cobalt and other raw materials. The poor availability of these metals and minerals linked to energy transformation has coined a new anglicism: greenflation. So while on the one hand we have the central banks scrambling to keep inflation close to the 2% target, on the other governments are pushing for a new world that would devour resources that will not soon be available and that could make Powell, Lagarde and Co.’s task harder.

If 3-year budget plans are difficult to make, it’s almost impossible to guess what could happen in the decades to come. In 2021 the FED and ECB were still talking of “transitory” inflation, only to use an opposite language only one year later. Nobody can foresee how the energy transformation process will evolve by 2050, however there are times along the way when we are comforted that the direction is the right one. The year 2023 is one such time.

The IEA published its 2023 Energy Report, stating that this year the investments in solar will exceed those in oil. Out of the 2.8 USD trillion that are going to be invested in energy sources the renewables, starting with solar panels, will account for 1.7 while fossil fuels will take the remaining 1.1: renewable investments will thus grow by 24% in 2021-23 vs +15% for fossil fuels.

Even in China, a country that is going to pollute more and more by 2030, renewables managed to pull ahead in 2023: the installed power from renewable sources reached 50.9%, more than fossil sources.

Another example comes from Tesla, although in this case it’s more of an equality: the cost per mile of the Model 3 reached the same level of the hugely successful Toyota Corolla. Of course, this is taking into account the government subsidies for electric vehicles.

Thus, the march towards a decarbonized world continues and, to help green fuels complete the overtaking of fossils, Europe issued in mid-June a new package on sustainable finance and the European Taxonomy.

Among the most innovative points of the package are the recommendations on transitional finance, that should help clarify which activities are to be considered as appropriate for a sustainable transition. This can be measured for example by the amount of taxonomy-aligned investments, so that big utilities whose investments are substantially targeting renewables can be easily distinguished by oil companies, whose green investments in 2022 were globally less than 5% of the total.

Another innovation is the introduction of new rules for ESG rating agencies. The sprouting of ESG data providers, whose wide-ranging methodologies end up in very different ratings for a given company, is one of the usual complaints of ESG-minded investors. A greater transparency by data providers and the prevention of potential conflicts of interest will lend more credibility to investment portfolios and allow end investors to have more confidence by reducing the fear of greenwashing.

That’s not all: the package sets new standards for the accounting of sustainability data by companies (CSRD) and issued new criteria for the economic activities that contribute to non-climate environmental objectives such as marine waters, circular economy, pollution prevention and control, biodiversity protection and restoration, etc. However there’s also a point as controversial as the introduction of gas and nuclear in the Taxonomy: the Defence sector. According to the new guidelines the investments in weapons and defence technologies are not in contrast with PAIs; indeed they are considered essential for the security of the EU, for peacekeeping and thus for the social sustainability! A rhetorical expedient arising from necessity, as what would be the purpose of weapons if no one had them?

The path that is shaping up in 2023 seems to go in the right direction. It’s important, though, not to lose credibility along the way by coercing temporary needs into the final goal.

With Next Generation EU, Repower EU and the Green Deal, the EU aims at becoming the first continent with net zero emissions by 2050. To reach the objective, Ursula Von der Leyen knows that Member States’ contributions are not enough: private investments are also necessary. To incentivise the latter, on one hand they have created the Taxonomy which defines the green business activities, and on the other hand they have introduced the SFDR, to categorise (article 6, 8, 9) the investment funds based on the level of “green” of their holdings. Two powerful instruments, when used together: companies have to align more and more to the European Taxonomy, and funds have to become greener and greener, going from art. 6 to art. 8, and from art. 8 to art. 9, to follow on the EU’s target.

In fact from 2019 to 2022 the sustainable funds (mainly art. 8 and to a lesser extent art. 9, that initially where simply called ESG) have grown exponentially and have now overcome the traditional ones (art. 6). The proliferation of art. 8 funds, a result of the limited restrictions to the investment universe compared to a traditional fund (the STOXX 600 ESG has 585 constituents, as opposed to 600 for the main index) has been accelerated by cosmetic adjustments to the existing art. 6 funds. This has negatively impacted the perception of investors, who have started to claim that many of such funds were simply “greenwashing”. Hence the need for a deeper distinction between art. 8 and art. 9 funds, ie between those who apply some ESG principles and those have to demonstrably quantify the sustainability of their own investments.

The regulation of art. 9 funds is however complicated, the rules have many gaps and they are subject to multiple interpretations, bringing up absurd consequences: some funds have to say that they have sustainable investments not taxonomy-aligned only because of lack of appropriate data, and a long/short fund cannot short non-sustainable companies because the investment universe must comprise only “sustainable” assets.

In addition the EU is tightening even more the rules for art. 9 funds to avoid them being associated to the “greenwashing” rage. Rather than clarifying the rules, the European Commission has increased the uncertainty surrounding them, pushing many investment houses to demote spontaneously their own art. 9 funds to art. 8 before January 2023, when the investment composition disclosures came into force. According to the Financial Times, in the last quarter of 2022 BNP Paribas, Blackrock, Amundi and Pictet have done so for about 175 €bn, shrinking the art. 9 funds assets by 40%.

The complexity of the regulation is so appalling, even at government level, that according to an end-of-March article of the Financial Times the European Commission is thinking about scrapping art. 9 altogether, citing sources close to the issue.

When you’re about to make a revolution, you go into uncharted territory: there are many obstacles and you can make many mistakes. But if the idea is good (who would argue that a greener world is not a good idea?), you have to persevere. Scrapping art. 9 funds would remove the main tool at the EU disposal to bring investors on board the energy transformation process. The investments in non-sustainable assets could last for a long time, the 2050 target would become utopic and Europe would lose credibility going back to have, as in the past decades, only a subordinate role at global level.

The US Inflation Reduction Act, approved last August and providing 369 USD bn at the disposal of green policies, has called for an EU response with Von der Leyen announcing “our European IR Act”.

Even though at the beginning the US bill has been seen favourably by the European Commission, with the same Von der Leyen congratulating the strong intervention towards climate change, the following scrutiny of its protectionist implications worried the EU members, that requested a joint EU-US task force to make them disappear. In the US IR Act, in fact, the tax credits benefit the products built predominantly within the US or countries that have specific commercial treaties with them, such as Canada or Mexico. One solution could be for European companies to move a substantial part of their business to the US, but that would jeopardize Europe’s attempt to regain the spotlight in the financial markets, missing the opportunity just on that one issue (the energy transformation) that it’s building its credibility upon.

Germany and France have not lost time in demanding more flexibility for state aid, something that would create resentment among countries financially more fragile, as pointed out by De Croo, Belgian Prime Minister, and Margrethe Vestager, European Commissioner for Competition.

As the joint task force proved to be ineffective, Von der Leyen announced at Davos the Green Deal Industrial Plan, intended to promote the development of net-zero technologies that are rapidly growing: a plan to re-assert its global leadership in this field.

Among the four pillars of the plan, investors focus on the first two: simplified and fast authorizations to accelerate the approval of objectives such as wind and solar farms, and a faster credit availability for strategic projects. The latter concerns the deregulation of state aid, that will have to be carefully balanced to avoid internal conflicts within EU member states, as well as a new sovereign fund, immediately criticized by the German Finance Minister who pointed out that loans within the Next Generation EU are still available but remain unused by many member states (Italy’s not one of them).

Among the net-zero technologies supported by the plan, we find batteries, solar panels, wind turbines, heat pumps, green electrolyzers, and carbon capture and storage facilities, in addition to the commodities necessary for their production.

The back-and-forth between US and EU on the development of green technologies will give a push to the companies involved in the sector. If the US IR Act provided a boost to their “renewable” companies, leaving the European ones a little behind, hopefully the EU answer will close the gap. Indeed, since the beginning of the year the sector has been performing very well: companies involved in building renovation and automation jumped by over 15% on average, the hydrogen pure plays by more than 25%, some companies active in the carbon capture by 30%, those producing power inverters and solar panels by 20%. However, wind companies remained behind, as well as big utilities that in this sparkling beginning of year have been mostly negative.

And so Europe, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the need for energy independence, responds with new impetus to the latest green challenge. Perhaps some compromise will be needed given the disparities between some member states, but when facing new difficulties the answer is always the same: promote and support with stronger urgency the energy transformation.

According to the UN the world population reached eight billion people on November 15th, 2022. The demand for food rises, deforestation gets worse, biodiversity decreases, terrains are drier and drier: all things that contribute to higher GHG emissions in the atmosphere. The UN estimate the whole food value chain represents 30% of global emissions, 40% of which come from agriculture and cattle breeding, fertilisers and pesticides; one third from changing use of soil; and the rest from the supply chain: cooking, refrigeration, packaging, transportation and waste, the latter amounting to one third of produced food. In addition, agriculture uses 70% of drink water and livestock farming 80% of farm terrains, contributing only for 20% of calories and 37% of proteins daily intake. And over 50% of antibiotics are used in agriculture and breeding, with an increased bacterial resistance as a result.

Without a change in our diet and our eating habits, where red meat outweighs fruits and vegetables, the Paris target is unattainable. And such changes would have a general health benefit considering the 2 billion people overweight or obese and another 2 billion suffering malnutrition.

Europe, with the program Farm to Fork, part of the Green Deal, was the first to start a re-thinking of the whole food value chain. Among the objectives by 2030: the reduction by 20% of fertilisers, 50% of pesticides and 50% of antibiotics; bring to 25% the farms dedicated to organic farming (it is now 7.5%); convert 10% of them where animals could prosper in the wild enhancing biodiversity; make 30% of lands and seas protected areas (only 26% of lands and 11% of seas are currently protected) and halve the food waste.

Member States don’t want to force people to eat as they think they should, but they can influence their decisions: mandatory labels about nutrition values and source of the food, avoid advertisements on low price meat that mask its quality, and use of a differential taxation depending on the product, such as the proposal of adding a 1€/kg tax on meat between 2023 and 2025, with a gradual increase. Moreover, Europe provides 30 billion euros of subsidies for livestock farming: if directed to cellular agriculture and production of vegetable-based food, that money could help with the desired transition. In fact, these two forms of alternative food production would reduce GHG emissions by 90% for a given meat production target, and ensure a limited use of water, pastures and other resources. On April 27th the EU Commission launched the initiative End the Slaughter Age, that demands to end the European subsidies for livestock farming and use the money for alternative ways of producing meat: the signatures collection started on June 5th. Perhaps the threshold of one million signatures won’t be reached within the first 12 months, but certainly it won’t remain an isolated attempt given Europe’s intention to spur sustainable foods.

Other types of incentives could be the carbon sequestration by farmers, include other sectors in the market for carbon certificates, use clean energy to produce food, anaerobic digestion for biogas produced by food waste.

Linked to this transformation are two important social aspects: a healthier treatment of animals and a lower use of child labor, as 75% of it globally happens precisely in the farming and breeding sectors.

The companies affected will be all those involved in the food chain: livestock farms, producers of fertilisers and enzymes, companies that produce and trade the products concerned, restaurants, start-ups of sustainable food, tech companies that produce tools for an agriculture more focused and sustainable, and pharma companies that make tests through the value chain.

Of all those, the transition will favour the companies producing enzymes and flavours and those that realize tests: the former will see their contribution to food production rise from the current 15% for traditional food to 85% for vegetable-based food; the latter will benefit from an increased control and a mandatory label for products sold in supermarkets.

Alternative foods are now more expensive than traditional foods, but we are comparing an industry in its infancy to one that benefits from large-scale production since decades, with optimized processes. It’s easy to see how the new industry will benefit from lower costs over time, as production increases, technologies improve, and for its ability to use 90% less resources.